“I was entertaining the fathers and the mothers of the people I sympathized with, and in some cases associated with, and whose point of view I shared,’ he recalled later, as quoted in the book “Going Too Far’ by Tony Hendra (Doubleday, 1987). “I was a traitor, in so many words. I was living a lie.’

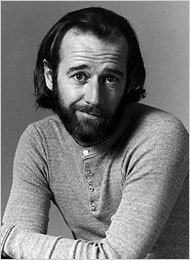

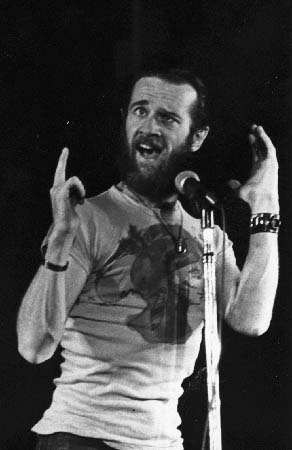

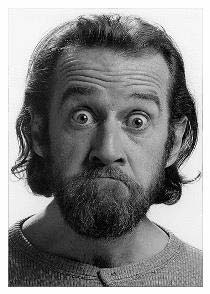

In 1970, Mr. Carlin staged a remarkable reversal of field, discarding his suit and tie, as well as the relatively conventional and clean-cut material that had catapulted him to the top. He reinvented himself, emerging with a beard, long hair, jeans and a routine steeped in drugs and insolence. A backlash followed; in one famous incident, he was advised to leave town when an angry audience threatened him at the Playboy Club in Lake Geneva, Wis., for joking about the Vietnam War. Afterward, he temporarily abandoned nightclubs for coffee houses and colleges, where he found a younger, hipper audience that was more attuned to both his new image and his material.

By 1972, when he released his second album, “FM & AM,’ his star was again on the rise. The album, which won a Grammy Award as best comedy recording, combined older material with his newer, more acerbic routines.

One, from “Class Clown,’ Mr. Carlin´s third album, became part of his “Seven Words You Can Never Say on Television,’ with its rhythmic recitation of obscenities. It was broadcast on the New York radio station WBAI. Acting on a complaint about the broadcast, the Federal Communications Commission issued an order prohibiting the words as “indecent.’ In 1978, the Supreme Court upheld the order, establishing a decency standard that remains in effect; it ensnared Howard Stern in 2005, precipitating his move to satellite radio.

Mr. Carlin refused to drop the bit and was arrested several times after reciting it onstage.

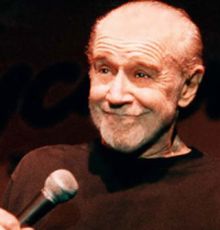

By the mid-´70s, like his comic predecessor Lenny Bruce and the fast-rising Richard Pryor, Mr. Carlin had emerged as a cultural renegade. In addition to his jests about religion and politics, he talked about using drugs, including LSD and peyote; he kicked cocaine, he said, not for moral or legal reasons but because he found “far more pain in the deal than pleasure.’