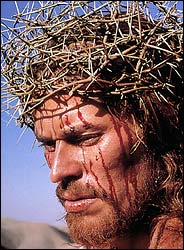

Imagining Jesus: Wilhelm Dafoe in "The Last Temptation of Christ" |

one for each culture that believes in him. |

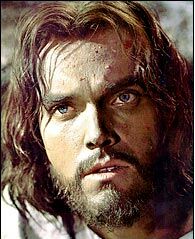

Imagining Jesus: Jeffrey Hunter in "King of Kings" |

Whatever arguments there may be about the verisimilitude of Mel Gibson's film "The Passion of the Christ," one thing is certain: this Jesus is a Hollywood hunk who probably bears little resemblance to what the Jesus of history looked like.

The title role is played by Jim Caviezel, a dark-haired, blue-eyed star whose brooding good looks have been compared to those of Montgomery Clift. He doesn't exactly fit the archaeological evidence that the average man of Jesus' day was about 5 feet 3 inches tall and a bantamlike 110 pounds. Given the harsh conditions, especially for working stiffs like the members of Jesus' family, combined with Jesus' ascetic lifestyle, which included walking everywhere, scholars agree that he was most likely a rather sinewy peasant, as tough as a root and about as appealing.

Not that portraying Jesus as a movie idol is anything new. Jeffrey Hunter in "King of Kings" (1961) is commonly referred to as "the Malibu Jesus," while Willem Dafoe's celluloid savior was a perfectly credible love match for the lusty Barbara Hershey as Mary Magdalene in "The Last Temptation of Christ" (1988). And Max von Sydow was a handsome — and distinctly Aryan — Jesus in "The Greatest Story Ever Told" (1965).

Of course, figuring out what Jesus really looked like is impossible. One reason is that the question apparently held almost no interest for Jesus' followers, who were Jewish and raised in a faith that strictly prohibited representations of the divine.

Still, within a few decades of Jesus' death, the issue cropped up again, both from natural curiosity and as a defense against those, like the second-century philosopher Celsus, who argued that Jesus would not have been divine because God could not take a corruptible human form.

"God is good, and beautiful, and blessed, and that in the best and most beautiful degree," Celsus wrote. "But if he come down among men, he must undergo a change, and a change from good to evil, from virtue to vice, from happiness to misery, and from best to worst."

Celsus, a Platonist from Alexandria, was expressing the prevailing view of the day. In the ancient world, the gods were supposed to be, well, godlike. They stood above and apart from mere mortals. They were great warriors and often great seducers. Celsus' arguments, however, were enough to inflame Christian apologists like Origen, who were facing nasty persecutions from the pagan empire.

But rather than fighting back by building Jesus up as some kind of super Zeus, Origen took the opposite tack. Jesus, he wrote in his lengthy treatise "Against Celsus," was no different from ordinary men of his day, and this ordinariness was in fact a proof of his divine humility, as well as a fulfillment of the prophecy in Isaiah 53, which says of the future messiah, "He hath no form nor comeliness; and when we shall see him, there is no beauty that we should desire him" (King James version).

A similar argument was used to refute early Christian heresies as well, especially those of the Gnostics, who often argued that Jesus was all spirit and did not become fully human. In his early-third-century polemic "On the Flesh of Christ," Tertullian was so insistent on Jesus' humanity that he said Jesus' "body did not reach even to human beauty, to say nothing of heavenly glory."

"The sufferings attested his human flesh," he continued, "the contumely proved its abject condition."

For some, Tertullian and his allies went too far in asserting Jesus' humanity over his divinity, and the dispute as to whether Jesus was either God or man, or, as the church authorities wanted it, both God and man, revealed through the mystery of the Incarnation, led to pitched theological battles. The matter wasn't settled until the end of the seventh century.

Subsequent church fathers tried to play down the interest in Jesus' looks as irrelevant, if not irreverent. But believers couldn't help wondering. The two most popular images of Jesus in the early Middle Ages were the anodyne representations of the face of Jesus on Veronica's veil (from vera icon, or "true icon"), the cloth that tradition says Veronica used to wipe Jesus' brow on the Via Crucis; and the Mandylion of Edessa, a disembodied portrait believed to have been reproduced without the intervention of human hands.

Actually creating an image of Jesus was a bit intimidating, but artists soon got over their jitters and began churning out pictures of him in a parade of images that brings renewed meaning to the phrase "infinite variety."

From the static yet profound icons of Eastern Orthodoxy to the punishing bruiser of Michelangelo's "Last Judgment" — which he consciously modeled on the Belvedere Apollo in the Vatican Museums — Jesus served the needs of the day. Slave-era blacks painted an African Jesus, and Chagall depicted Jesus as a victim of a pogrom, a tallit (Jewish prayer shawl) for a loincloth. Jesus took on almond eyes in Asia and blond hair in Scandinavia.

The consistent trend has been to make him more human, to move away from the remote, Godlike Christ, so as to render a Jesus that his followers could identify with. Caravaggio did it for Italians in the 17th century with a suffering, peasant Jesus, and the filmmaker Kevin Smith reflected the contemporary "Jesus is my best friend" mentality by introducing a smiling "Buddy Christ" in his 1999 theological romp, "Dogma."

Trying to run back through the gantlet of images and icons built up over the centuries and rediscover the true face of Jesus is no mean feat. While filming a new documentary about the historical Jesus ("The Mystery of Jesus" on "CNN Presents," tomorrow night at 8, Eastern time; 7, Central time; and 5, Pacific time), our production team sought the most accurate idea of what Jesus might have looked like. We chose a retired British medical artist, Richard Neave, who has made a career out of reconstructing the faces of famous historical figures from scant archaeological traces. Mr. Neave had worked with the BBC on a similar project a few years before, making a composite cast of three Semitic skulls from first-century Palestine and using them as the basis for fleshing out the face of a contemporary of Jesus, if not Jesus himself.

The facial overlay that the BBC then put on Mr. Neave's work didn't please him or many others, however. He wasn't upset that some thought that the face made Jesus look like a New York taxi driver. Rather, he didn't like the eyes and the mouth, and what the historian Robin M. Jensen, writing recently in Christian Century, called "a particular dumbfounded — one might say stupid — expression."

How a short, thin man may have been made an imposing presence.

Hoping to rectify the problem, we hired a New York artist, Donato Giancola, and reworked the portrait, using Mr. Neave's skull and information from other experts. The results, to my mind, were a more noble, even soulful, Jesus, and yet historically believable — I hope something closer to the itinerant Galilean of history. Even so, the results looked uncannily like Mr. Giancola himself, which was part coincidence — he actually resembles the face Mr. Neave produced — and part inevitability. Artists are always painting themselves, just as believers are always making themselves the models for the divine.

Five centuries before Christ, the Greek philosopher and poet Xenophanes satirized humanity's tendency to make gods in their own image. The Ethiopians fashion dark-skinned gods, he wrote, the Thracians gods with pale skins and red hair. "And if oxen and horses or lions had hands," he famously wrote, "and could paint with their hands, and produce works of art as men do, horses would paint the forms of the gods like horses, and oxen like oxen."

Steve Humphries-Brooks, a professor who teaches a course called "Celluloid Savior" at Hamilton College, says that while public furor in the United States "has always been over the `authenticity' of the Hollywood Jesus, the overlooked issue is really what this Jesus says about America, where we are and where we are going."

The rise of a sedentary leisure class in the 19th century, for example, spurred worries that Christians were getting soft along with their faith. The "muscular Christianity" movement and the Y.M.C.A. network that it inspired emerged as one means to develop strapping Christian men of military bearing and to rescue the faith from what the preacher Billy Sunday called the prevailing "flabby-cheeked, brittle-boned, weak-kneed, thin-skinned, pliable, plastic, spineless, effeminate, sissified, three-carat Christianity."

As Stephen Prothero recounts in his insightful and entertaining new book, "American Jesus: How the Son of God Became a National Icon" (Farrar, Straus & Giroux), one of a number of recent cultural histories about the peculiarly American version of Jesus, Christian leaders in the early 20th century were positively obsessed with counteracting the image of a Christ of "womanly sweetness," as one pastor described popular representations, or, as another put it, a "namby-pamby effeminate" Jesus.

In 1940 an obscure Chicago ad man and evangelical Christian, Warner Sallman, was inspired to paint a portrait of Jesus by an art teacher who exhorted him to depict a "virile, manly Christ" who "faced Calvary in triumph." The result was Sallman's famous "Head of Christ," which was distributed to World War II soldiers and eventually became the most popular Jesus representation ever, with more than 500 million copies in circulation.

In this sense, Mr. Gibson's "Passion" can be seen as another round in a more than century-old battle to assure Americans that Jesus was a manly savior, and that real men could be good Christians. Mr. Gibson's Jesus is a kind of "triumphant action hero," in Mr. Humphries-Brooks's words, who can represent a tough-minded America for tough times.

Christians have always responded to powerful images as much as they have to the written word. Yet the "true" face of Jesus is in fact a blank canvas, or a palimpsest that each generation rewrites as a way to define what its faith means. David Gibson is the author of "The Coming Catholic Church" and co-producer of "The Mystery of Jesus." As far as he knows, he is not related to Mel Gibson.

Copyright 2004 The New York Times Company.